三甲

三甲

临界髋关节发育不良Borderline DDH (2):疼痛性临界髋关节发育不良的治疗

临界髋关节发育不良Borderline DDH (2):疼痛性临界髋关节发育不良的治疗

作者:Michael C Wyatt, Martin Beck.

作者单位: Klinik für Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie Luzerner Kantonsspital 6004 Luzern, Switzerland.

译者:陶可(北京大学人民医院骨关节科)

摘要

在过去的几十年里,影像技术的改进和手术技术的进步使得保髋手术得到了快速发展。然而,疼痛性临界髋关节发育不良的治疗仍然存在争议。在这篇评论中,我们将确定相关问题并描述患者评估和治疗方案。我们将提供自己的建议,并确定未来的研究领域。

简介

在过去的几十年里,髋关节生物力学知识的提高和手术技术的进步使得保髋手术得到了快速发展。保髋手术适应范围广泛,从髋臼浅且不稳定的髋关节到髋臼深且患有股骨髋臼撞击(FAI)的髋关节。虽然人们普遍认为,不稳定髋关节发育不良的最佳治疗方法是重新定位髋臼以增加覆盖范围,但人们同样认为,必须减小过度覆盖的髋臼临界以消除撞击。所有这些髋关节都可能存在凸轮畸形,需要在手术矫正时加以解决[1]。在最极端的情况下,所需的治疗是显而易见的。然而,有一个过渡区,很难区分不稳定性和股骨髋臼撞击(FAI)。过去,这些髋关节被称为“临界”髋关节。通常,这包括外侧中心临界(LCE)角度在20°到25°之间的髋关节[2]。然而,“临界”一词是有问题的,因为它是一个放射学定义,只涉及描述髋关节稳定性的几个重要参数之一。髋臼顶倾斜角、前后覆盖和股骨前倾是应纳入髋关节稳定性分析的其他因素。

髋关节发育不良与髋关节骨关节炎之间的关联已经确定[3, 4],有不稳定迹象的髋关节发育不良退化速度更快[5]。临界髋关节可能不稳定、撞击或两者兼而有之。临界髋关节发育不良的稳定性很难确定,并且容易受个人主观影响,骨科界普遍倾向于低估不稳定性,从而导致不适当的治疗。最近的研究表明,对患有临界发育不良(LCEA > 20°)的患者进行关节镜髋关节手术(包括盂唇修复和关节囊折叠缝合术)可能会在短期内带来适当的改善[3, 4]。然而,有证据表明,之前错误的髋关节镜检查会对此类髋关节的治疗结果产生负面影响[6]。

因此,疼痛性临界髋关节发育不良的治疗仍然是一个极具争议的问题。临界性髋关节发育不良在患有髋关节疼痛的年轻人中很常见,在选定的患者群中报告的患病率为37.6%[7]。在临界髋关节发育不良中,可能与其他不稳定原因(如韧带松弛症)有显著重叠[8]。然而,根本问题是难以正确分类潜在的病理生物力学。

定义

第一个问题在于定义。在前后位骨盆X线片[9] (LCEA)上测量的Wiberg外侧中心边缘角传统上用于将髋关节分类为正常(LCEA >25°)、发育不良(LCEA <20°)或临界(LCEA 20–25°),尽管这些定义值在文献中差异很大[3, 10]。然而,使用外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)存在两个问题。

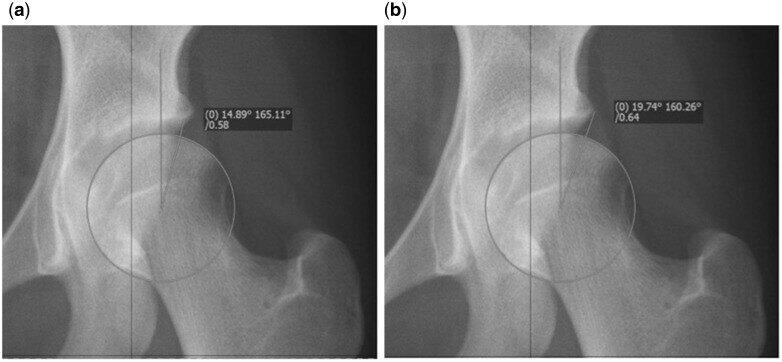

首先是测量方法。为了测量外侧中心边缘角(LCEA),首先通过与股骨头轮廓相符的圆来定义股骨头的中心。角度的第一个分支垂直穿过旋转中心。第二个分支由股骨头的中心和股骨最外侧点定义(图1a)。重要的是不要使用髋臼的最外侧点(图1b),因为这不符合Wiberg的定义,并且会给出错误的高值(外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)偏大)[11]。

Fig. 1.(a) Correct measurement of the LCEA using the edge of the sourcil, indicating moderate dysplasia. (b) Incorrect measurement of the LCEA in the same hip. Using this value would falsely classify this hip as borderline.

图1(a)使用髋臼临界正确测量外侧中心边缘角(LCEA),表明中度髋关节发育不良。(b)同一髋关节的外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)测量不正确。使用此值会错误地将此髋关节归类为临界。

其次,实际术语“临界髋关节发育不良”是由Wiberg本人首次提出的,包括外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)在20°和25°之间的髋关节[2]。外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)是一种放射学测量,本身无法预测临界髋关节发育不良的稳定性,也无法完全描述股骨头覆盖范围。因此,外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)无法指导手术决策[12–14]。部分原因是外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)本身无法涵盖发育不良的精确位置,并且忽略了前后股骨头覆盖范围。此外,髋臼指数(AI)和股骨前倾等其他参数也与髋关节稳定性密切相关。如果外侧中心边缘角(LCEA)减少,AI可能正常,在这种情况下很难评估髋关节的稳定性[15]。另一方面,股骨前倾过度可能会加剧髋关节前部不稳定[16]。

根本问题是什么?

对于疼痛的临界髋关节发育不良,很难仅通过二维射线测量将病理机制表征为撞击(稳定)或发育不良(不稳定),尤其是仅由髋臼功能决定而不考虑股骨的测量。髋关节稳定性的功能表征对于指导手术决策至关重要。不稳定髋关节从逻辑上可以从髋臼重新定向截骨术中受益,而稳定髋关节可以从撞击手术(如股骨凸轮骨成形术)中受益。

那么关于髋关节内病理学的了解有多少?应该如何评估这些患者?有哪些治疗方案?手术结果如何?这组患者的潜在隐患是什么?未来的发展方向是什么?在这篇叙述性综述文章中,我们旨在解决这些问题,并阐明这组具有挑战性的患者的处理方法。

髋关节发育不良和临界髋关节不稳定的潜在病理是什么?

髋关节发育不良患者的关节接触压力异常增高,股骨头(软骨损伤,导致软骨下)骨质相对暴露。髋臼通常较浅且前倾,盂唇经常有代偿性增大,但同时伴有髋臼后倾的情况也很高[17]。股骨通常呈外翻,前倾度高[10]。这些异常的解剖特征会导致病理性髋关节生物力学,表现为盂唇撕裂、软骨损伤和髋关节不稳定,这些很容易被误解为撞击。由于骨稳定性受损,软组织稳定器(即纤维软骨盂唇和髋关节囊)的重要性就凸显出来[18]。一旦软组织约束失效,髋关节就会变得不稳定。然而,我们必须明白,主要的潜在病理是缺乏骨性稳定性,这会导致髋关节失效,而不是软组织稳定性失效。

半脱位髋关节发育不良的自然病史预后非常差,并且必然会导致关节退化[5]。恶化速度与半脱位严重程度和患者年龄直接相关,通常在症状出现后约10年,就会出现严重的退行性变化[19]。在没有半脱位的情况下,自然病史很难预测退化速度。临界髋关节发育不良也是如此。最近的一项研究强调了髋臼覆盖的重要性。在一项为期20年的大型女性队列研究中,研究显示,如果外侧中心边缘角(LCE)低于28°,则每降低一度,放射学OA风险就会增加13%[20]。因此,除了短期缓解症状外,还必须考虑长期可能的发展。

临床表现

临界髋关节发育不良的临床表现与其他年轻活跃成人髋关节疾病(如FAI综合征[21])非常相似,因此,彻底的病史、体格检查和放射学评估对于正确诊断这些患者至关重要。

病史

重点记录病史。临界髋关节发育不良患者的主要症状是疼痛。这通常发生在腹股沟和髋关节外侧,但也可能发生在臀部(臀后区)。有必要记录完整的疼痛病史。寻找特定的不稳定和“避免疼痛”症状,这可能表明已经达到因缺乏骨性稳定性而需要的软组织代偿的极限。咔嗒声和卡住的症状也很常见。此外,还会询问患者是否有任何迹象表明患者已经患上髋关节炎,例如夜间疼痛。症状应结合患者的功能限制和已经接受的医疗护理,包括物理治疗、药物、其他意见和手术。

检查

随后应进行髋关节的合理临床检查,包括恐惧试验和撞击测试。患者通常会表现出“膝内翻”步态,同时伴有髋关节内收肌力矩增加和髋关节内旋增加,这与股骨前倾增加一致。为了功能性地增加前覆盖,可能存在前凸过度。应确定大转子处有无压痛[22]。

务必记住检查患者的旋转轮廓、进行神经血管检查以及检查全身关节松弛的迹象,并使用Beighton评分对此进行量化。具体关键目标包括排除(i)晚期退化过程的存在,例如表现为固定屈曲畸形和运动范围减少,以及(ii)其他病理,例如腰椎病或L5神经根病引起的疼痛。

调查

诊断成像应从骨盆的标准化AP平片和股骨颈侧位片(穿桌侧位、Dunn位、假斜位)[23]开始。仔细检查这些图像以测量LCEA、AI、挤压指数、股骨颈干角和FEAR指数(见下文)。应确定骨关节炎的Tonnis等级以及是否存在凸轮形态。应仔细检查不稳定的直接迹象,这些迹象包括股骨头移位,可通过与髂坐线的距离增加、Shenton线断裂和AP视图上股骨头重新定位来识别,髋关节处于外展状态,使用MR关节造影时后关节间隙中有钆,这表明股骨头向前移位,因此不稳定。FEAR指数与不稳定性有很高的相关性(见下文)。必须精确测量和记录各种参数。

有必要使用三维计算机断层扫描(CT)进行横断面成像,以获得有关骨解剖结构和发育不良位置的精确信息,包括髋关节周围囊肿的存在和位置[24-26]。此外,CT还应包括股骨前倾的评估,如果前倾过大,可能会加剧髋关节前部不稳定。磁共振成像(MR-关节造影)应遵循专门的髋关节检查方案,包括径向图像采集或重建和关节内造影剂应用[27],以检查关节内结构和盂唇和关节软骨的病理。可以区分引起类似症状的其他原因,例如缺血性坏死、转子滑囊炎或臀肌病变。其他测量包括盂唇大小[13, 28]和髂关节囊体积[29]。对于这些患者,我们还提倡进行非牵引性MR关节造影检查,以检查是否存在钆积聚,即所谓的“新月征”,这是轴向视图上不稳定的细微征兆[30]。

这些测量值的价值是什么?

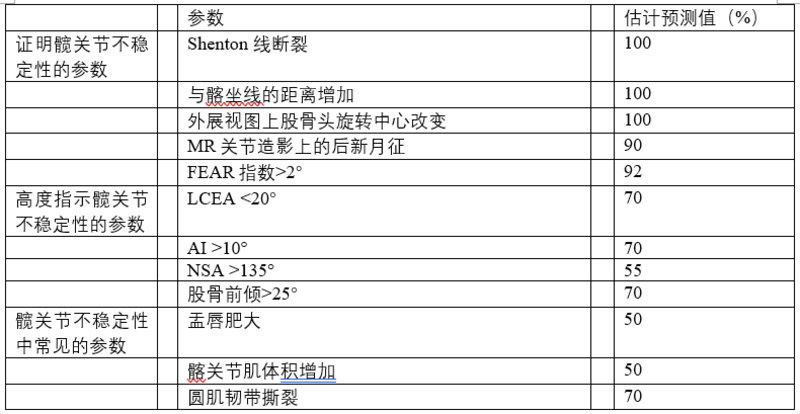

在平片上,那些直接表明不稳定的测量值是股骨头移位,与髂坐线的距离增加,Shenton线断裂,髋关节外展时AP视图上股骨头重新定位,以及FEAR指数。在MR关节造影中,后下关节间隙中钆的存在表明股骨头移位,因此不稳定。AI、NSA、AT、高髂囊体积和盂唇体积可能存在增加,但不能预测不稳定性[30](表1)。

表1. 用于评估髋关节不稳定性的各种参数概述

The Femoro-Epiphyseal Acetabular Roof (FEAR) index: 股骨骨骺髋臼顶指数

The femoral neck-shaft angle (NSA): 颈干角

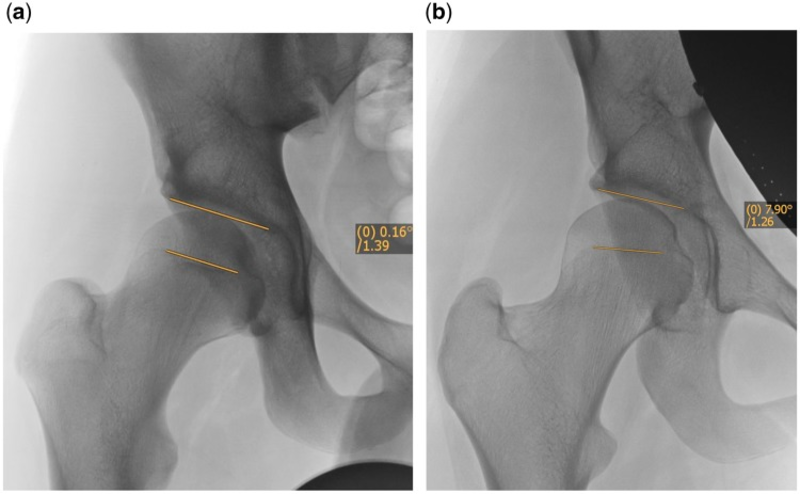

FEAR指数是最近描述的参数,似乎对预测髋关节稳定性具有很高的价值[27]。它是由髋臼顶与股骨生长板中央1/3处之间的角度形成的(图2)。其依据是:在生长过程中,股骨的骨骺生长板会垂直于髋关节的关节反作用力。股骨颈的生长和方向受股骨颈下生长板的控制[31]。Pauwels和Maquet[32]提出理论,合力作用于骨骺软骨的中心,在生长过程中,根据Heuter-Volkman原理,骨骺板会垂直于关节反作用力。Pauwels和Maquet的理论后来得到了Carter等人[33]的证实,他们通过二维有限元分析研究了髋关节负荷的影响。闭合的骨骺板的角度表示跨股骨近端骨骺[34]的力的平衡,也表示跨关节力在过去的作用方式。因此,它是一个功能参数,反映了髋关节在生长过程中长期的关节反作用力。如果FEAR <0°,则认为髋关节稳定。统计分析表明,5°的临界值预测稳定性的概率为80°。最近的研究表明,2°的临界值预测稳定性的概率为90%(Batailler等人,正在准备发表中)。使用FEAR指数的案例如图3a和b所示。

Fig. 2.The FEAR index. The angle is measured between a line connecting the most medial and lateral point of the sourcil and a line connecting the medial and lateral end of the straight part (usually central third) of the physeal scar of the femoral head. A negative FEAR index, with the angle opening medially as shown in Fig. 3a, indicates a stable hip.

图2. FEAR指数。测量连接股骨最内侧和外侧点的线与连接股骨头骨骺直线部分(通常为中央三分之一)内侧和外侧端的线之间的角度。如图3a所示,角度向内侧打开的阴性FEAR指数,表示髋关节稳定。

Fig. 3.(a) Case examples using the FEAR index. 17-year-old male, LCEA 20°, FEAR 0°. Hip deemed therefore stable and patient managed with hip arthroscopy. (b) Case examples using the FEAR index. 17-year-old female, LCEA 20°, FEAR 8°. Hip deemed therefore unstable and patient managed with PAO.

图3. (a)使用FEAR指数的病例。17岁男性,LCEA 20°,FEAR 0°。因此髋关节稳定,患者接受髋关节镜治疗。

(b)使用FEAR指数的病例。17岁女性,LCEA 20°,FEAR 8°。因此髋关节不稳定,患者接受PAO截骨治疗。

有哪些治疗方案?

治疗取决于髋关节的稳定性。疼痛性临界髋关节发育不良的治疗方案包括非手术治疗、解决关节内撞击的手术治疗(通过髋关节镜或髋关节外科脱位进行的FAI手术)和解决不稳定性的手术治疗(采用PAO和/或股骨截骨术的重新定位截骨术)(见图2)。非手术治疗包括患者教育、活动调整、简单的止痛药、非甾体抗炎药和髋关节腔内注射药物[35]。有针对性的物理治疗可以改善肌肉调节、疼痛和本体感受控制。

以下段落将讨论包括关节镜和/或截骨术的临界髋关节发育不良的手术治疗方案。

这组患者接受髋关节镜检查的结果如何?

随着髋关节镜技术的最新发展,许多外科医生正在使用它来治疗临界髋关节发育不良,尤其是因为人们认为髋臼周围截骨术等替代技术的风险更高,术后恢复时间更长。临界髋关节发育不良的髋关节镜检查还可以让外科医生处理髋关节内病变,如盂唇撕裂或股骨凸轮畸形 [3, 12, 36]。如果考虑使用 PAO 来解决骨稳定性不足的问题,那么关节镜检查不仅可以让外科医生了解髋关节的关节内状态,还可以了解患者在随后进行更大规模手术时的表现 [37]。然而,关于临界髋关节发育不良的髋关节镜检查的已发表文献很少,而且短期随访也存在局限性。

在 Jo 等的系统综述中,确定了 13 项关于髋关节发育不良的关节镜检查的研究 [10]。这些研究各不相同,所有研究都是病例系列。仅有6项研究报告了主观和/或客观结果。关节镜检查的手术指征不明确,患者事先接受过多种非手术治疗。此外,临界髋关节发育不良的确切定义各不相同,只有两项研究使用了 Byrd 和 Jones 的定义 [36]。三项研究报告了髋关节镜作为辅助工具,三项研究报告了髋关节镜作为独立治疗。盂唇撕裂的总患病率为 77.3%,主要位于髋臼缘的前部或前上部。髋臼软骨病变比股骨病变更常见(59-75.2% 比 11-32%),并且位于盂唇病变的邻近。

仅有两项研究检查了临界髋关节发育不良病例(LCEA 20-25°)的关节镜检查结果,其中只有一项描述了患者报告的结果测量。后者是 Byrd 和 Jones [36] 的前瞻性临床病例系列,其中 66% 的髋关节(32 髋)患有临界髋关节发育不良。关节镜检查后,平均改良Harris髋关节评分从 50(差)改善到 77(一般)。作者得出结论,髋关节镜治疗可能解决髋关节内病理而不是发育不良的放射学证据的结果。

对临界髋关节发育不良进行髋关节镜检查有什么危险?

临界髋关节发育不良患者进行关节镜盂唇切除术和髋臼外侧缘切除术可导致爆发性髋关节不稳定 [38]。即使修复了盂唇,也必须保留髂股韧带和髋关节的其他静态稳定器,以防止不可逆的后果或导致髋关节不稳定[39–41]。没有确凿的文献支持在这些情况下进行关节囊修复,但这似乎是一种安全合理的做法[42]。关节囊复位技术可提高临界髋关节发育不良的稳定性[12]。如果髋关节在术前足够不稳定,那么仅通过髋关节镜治疗关节内病变是不够的,患者将需要进行PAO截骨术[43, 44]。必须记住,髋关节的稳定性首先取决于髋骨几何形状。在轻微不稳定(临界发育不良)中,稳定性可能由次级软组织结构来确保。一旦这些结构因微创伤或大创伤而失效,髋关节就会变得不稳定。恢复软组织稳定性可能只会在短时间内改善髋关节稳定性,但软组织很可能再次磨损。因此,必须首先解决潜在的骨病理问题,才能取得良好的长期效果。

最近的一份报告显示,髋关节发育不良患者在髋关节镜检查失败后,PAO的髋关节特定功能结果较差[6]。因此,对这组患者单独进行髋关节镜检查应谨慎处理。但是,对于那些由于髋关节状况不佳(即 AI 和股骨前倾正常)或高龄(即>40 岁)而不适合进行 PAO 的患者,它可能有用。

重新定向髋臼周围截骨术对这组患者有何影响?

通过髋臼周围截骨术进行髋臼重新定向已成为髋关节发育不良最常见的治疗方法,据报道术后20多年效果良好。传统上,PAO时关节内病变的处理方法是进行前关节切开术。然而,随着PAO微创技术的发展,情况已不再如此。微创PAO技术缩短了术后恢复时间[45]。

最近的一项研究表明,一些可改变的因素,例如较高的体力活动量和较高的BMI(大于30 kg/m2)可导致PAO的发病年龄下降[46]。此外,患有较重发育不良程度的患者患PAO的年龄也较早:LCEA是手术年龄的独立预测因素,即LCEA较低的患者往往需要在较早的年龄接受PAO手术。但是,轻度和中度发育不良患者的PAO预后没有差异。在本研究中,轻度发育不良被归类为15-25°,这涵盖了我们对临界髋关节发育不良的定义。最近的一项多中心前瞻性队列研究检查了患者报告的PAO结果指标,结果表明,虽然总体结果良好,但临界髋关节发育不良患者和男性的改善程度低于发育较重的患者[47]。作者讨论了小范围矫正的危险,这可能导致过度矫正和医源性FAI、股骨前倾增加和软组织松弛。

建议和未来方向

在临界髋关节中,关键步骤是确定稳定性。关于髋关节的稳定性,只有两种情况:髋关节稳定或不稳定。没有中间状态。如果接受这个概念,治疗就会变得相对简单。不稳定可能与其他病症(如FAI或超负荷/过度使用和软骨疾病)相结合,需要同时治疗。如果髋关节不稳定,则需要髋臼重新定位。仅解决磨损的二级稳定器并不能解决潜在的生物力学问题,最多只能产生令人满意的短期结果。在稳定的髋关节中,可以进行开放或关节镜关节保留手术。然而,我们必须记住,低于28°的LCE角度每减少一度,骨关节炎的发病率就会增加13%[20]。因此,如果有疑问,为了最大限度地提高获得良好长期结果的机会,我们主张进行髋臼重新定向PAO截骨手术。

重要的是要确定我们缺乏知识的领域,以指导进一步的研究。将对这些患者进行长期随访研究,比较髋臼重新定向和髋关节镜检查,理想情况下,将记录所有成像参数和Beighton评分。此外,还应获得患者报告的结果测量和恢复时间,以及包括运动在内的活动恢复时间。

The FEAR index is a recently described parameter that seems to have a high value to predict stability of the hip [27]. It is formed by the angle between the acetabular roof and the central third of the femoral growth plate (Fig. 2). It is based on the fact that during growth the epiphyseal growth plate of the femur orients itself perpendicularly to the joint reacting forces of the hip. Growth and the orientation of the femoral neck are under the control of the subcapital growth plate [31]. Pauwels and Maquet [32] theorized that the resultant force acts from the center of the epiphyseal cartilage and that during growth, the epiphyseal plate orients itself perpendicular to the joint reaction force in accordance with the Heuter–Volkman principle. Pauwels and Maquet’s theory later was confirmed by Carter et al. [33] who studied the influence of hip loading by bi-dimensional finite element analysis. The angle of the closed epiphyseal plate indicates the balance of forces across the proximal femoral physis [34] and indicates how the transarticular forces acted in the past. Therefore, it is a functional parameter that reflects the joint reacting forces over a long period of time during growth of the hip. If the FEAR is <0° the hip is considered stable. Statistical analysis has shown that a cutoff value of 5° predicts stability with 80° probability. More recent work has shown that a cutoff value of 2° predicts stability with 90% probability (Batailler et al., in preparation). Case examples of using the FEAR index are shown in Fig. 3a and b.

The management of the painful borderline dysplastic hip

Abstract

Improved imaging and the evolution of surgical techniques have permitted a rapid growth in hip preservation surgery over the last few decades. The management of the painful borderline dysplastic hip however remains controversial. In this review, we will identify the pertinent issues and describe the patient assessment and treatment options. We will provide our own recommendations and also identify future areas for research.

INTRODUCTION

Improved knowledge about hip biomechanics and the evolution of surgical techniques have permitted a rapid growth in hip preservation surgery over the last few decades. The spectrum covers a wide range from hips with shallow acetabuli, which are unstable, to hips with deep acetabuli that are suffering from femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI). While there is a general agreement that the best treatment for the unstable dysplastic hip is a reorientation of the acetabulum to increase cover, there is equal agreement that the rim of the over-covering acetabulum has to be reduced to remove impingement. On all those hips a cam deformity may be present that needs to be addressed at the time of surgical correction [1]. At the far ends of the spectrum the requisite treatment is obvious. However, there is a transition zone where it is difficult to discriminate instability from FAI. In the past these hips were referred to as ‘borderline’ hips. Usually, this included hips with a lateral center edge (LCE) angle between 20° and 25° [2]. However, the term ‘borderline’ is problematic, because it is a radiographic definition and only addresses one of several parameters important to describe hip stability. Acetabular roof obliquity, anterior and posterior cover and femoral antetorsion are other factors that should be included into an analysis of hip stability.

The association of hip dysplasia with hip osteoarthritis is established [3, 4] and dysplastic hips with signs of instability degenerate at a higher rate [5]. A borderline hip can either be unstable, impinging or maybe both. The stability of the borderline is difficult to determine and subject to interpretation with a general tendency in the orthopaedic community to underestimate instability that then leads to inappropriate treatment. Recent studies suggest that arthroscopic hip surgery with labral repair and capsular plication in patients with borderline dysplasia (LCEA > 20°) may result in appropriate short-term improvements [3, 4]. However, there is evidence that a wrongly done previous hip arthroscopy has a negative impact on the outcome on the treatment of such hips [6].

Therefore, the management of the painful borderline dysplastic hip however remains an issue of great controversy. Borderline hip dysplasia is common in young adults with hip pain with a reported prevalence of 37.6% in selected patient cohorts [7]. In the borderline dysplastic hip there may be significant overlap with other causes of instability such as connective tissue laxity [8]. However, the fundamental issue is the difficulty in correctly classifying the underlying patho-biomechanics.

DEFINITION

The first problem lies in the definition. The Lateral Centre Edge Angle of Wiberg as measured on an Antero-posterior pelvic radiograph [9] (LCEA) has traditionally been used to classify hips as normal (LCEA >25°), dysplastic (LCEA <20°) or borderline (LCEA 20–25°) although these defining values vary widely in the literature [3, 10]. However, the use of the LCEA has two problems.

Firstly the method by which it should be measured. To measure the LCEA the center of the femoral head is first defined by a circle fitting the contour of the femoral head. The first branch of the angle runs perpendicular through the center of rotation. The second branch is defined by the center of the femoral head and the most lateral point of the sourcil (Fig. 1a). It is important not to use the most lateral point of the acetabulum (Fig. 1b), because this does not follow the definition of Wiberg, and will give false high values [11].

Secondly the actual term ‘Borderline hip dysplasia’ was first introduced by Wiberg himself, including hips with a LCEA between 20° and 25° [2]. LCEA is a radiographic measure and per se cannot predict stability in the borderline dysplastic hip nor does fully describe femoral head coverage. Therefore the LCEA cannot direct surgical decision making [12–14]. Part of the reason is that LCEA alone does not encompass the precise location of dysplasia and disregards anterior and posterior femoral head coverage. Also other parameters such as acetabular index (AI) and femoral antetorsion are very relevant for stability of the hip. In the presence of a decreased LCEA AI may be normal in which case the stability of the hip is difficult to assess [15]. On the other hand, excessive femoral anteversion may potentiate anterior hip instability [16].

WHAT IS THE FUNDAMENTAL ISSUE?

In the painful borderline dysplastic hip it is difficult to characterize the pathological mechanism as impingement (stable) or dysplasia (unstable) by a two-dimensional radiographic measurement alone, especially one that is solely a function of the acetabulum and takes no account of the femur. This functional characterization of hip stability is of paramount importance to guide surgical decision-making. An unstable hip would logically benefit from acetabular reorientation osteotomy whilst a stable hip would benefit from impingement surgery such as femoral cam osteoplasty.

So what is known about the intra-articular pathology? How should these patients be assessed? What are the treatment options? What are the surgical outcomes? What are the potential pitfalls with this group of patients? What are the future directions? In this narrative review article we aim to address these questions and elucidate the management of this challenging group of patients.

WHAT IS THE UNDERLYING PATHOLOGY OF HIP DYSPLASIA AND UNSTABLE BORDERLINE HIPS?

In hip dysplasia, there are abnormally high articular contact pressures and relative bony uncovering of the femoral head. The acetabulum is typically shallow and anteverted with an often compensatory enlarged labrum, but there is also a high prevalence of concomitant acetabular retroversion [17]. The femur is classically in valgus with high antetorsion [10]. These abnormal anatomical features cause pathological hip biomechanics which manifest as labral tears, chondral lesions, and hip instability, which can easily be misinterpreted as impingement. As the osseous stability is compromised the importance of the soft tissue stabilisers, namely the fibrocartilaginous labrum and the hip capsule, is accentuated [18]. Once the soft tissue constraints fail then the hip becomes unstable. However, one has to understand that the principal underlying pathology is the lack of osseous stability, which leads to failure of the hip and not the failing soft tissue stability.

The natural history of the subluxing dysplastic hip is a very poor prognosis and invariably leads to joint degeneration [5]. The rate of deterioration is directly related to subluxation severity and patient age and usually about 10 years after onset of symptoms severe degenerative changes have developed [19]. The natural history in the absence of subluxation is more difficult to predict concerning the speed of degeneration. The same accounts for borderline dysplastic hips. A recent study highlights the importance of acetabular cover. In a large cohort of females, followed for 20 years, it was shown that each degree reduction in LCE below 28° is associated with 13% increased risk of radiographic OA [20]. Therefore, besides short-term relief of symptoms, the long-term possible evolution has to be kept in mind.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of borderline acetabular dysplasia is very similar to that of other young active adult hip disorders, such as FAI syndrome [21] so a thorough history, physical examination, and radiographic evaluation are essential to properly diagnose these patients.

HISTORY

A focused history is taken. The primary symptom in patients with borderline hip dysplasia is pain. This is typically perceived in groin and lateral hip but can also be in the buttock. A full pain history is warranted. Particular symptoms of instability and ‘giving way’ are sought that may indicate that the limits of soft tissue compensation for a lack of osseous stability have been reached. Symptoms of clicking and catching are also common. Furthermore any indications that the patient has established hip arthritis, such as night pain, are asked for. The symptoms should be put into the context of the patient’s functional limitations and medical attention already received including physiotherapy, medications, other opinions and surgery.

EXAMINATION

A logical clinical examination of the hip should follow including apprehension and impingement tests. The patient will often display a ‘kneeing-in’ gait in association with an increased hip adductor moment and increased internal hip rotation consistent with increased femoral antetorsion. Hyperlordosis may be present in order to functionally increase anterior cover. Tenderness over the greater trochanter should be determined [22].

It is crucial to remember to examine the patient’s rotational profile, perform a neurovascular examination and to check for signs of generalized joint laxity and quantify this using Beighton’s score. Specific key aims include refuting the presence of (i) an advanced degenerative process manifest for example with fixed flexion deformity and decreased range of motion and (ii) alternative pathology such as pain referred from lumbar spondylosis or L5 radiculopathy.

INVESTIGATIONS

Diagnostic imaging should commence with standardized plain AP radiograph of the pelvis and a lateral femoral neck views (lateral cross table, Dunn view, false profile views) [23]. These images are scrutinized to measure the LCEA, AI, extrusion index, femoral neck-shaft angle and FEAR index (see below). The Tonnis grade of osteoarthritis should be determined along with whether there is cam morphology. Direct signs of instability should be scrutinized for and these comprise femoral head migration, recognized by an increased distance from the ilioischial line, a break in Shenton’s line and recentering of the femoral head on an AP view with the hip in abduction and Gadolinium in the posterior joint space when using MR-arthrography, that indicates anterior migration and thus instability of the femoral head. The FEAR index has a high association with instability (see below). The various parameters have to be measured precisely and recorded.

Cross-sectional imaging with three-dimensional computerized tomography (CT) for precise information on bony anatomy and location of dysplasia including the presence and location of periarticular cysts is warranted [24–26]. Furthermore CT should include estimation of femoral antetorsion which, if high may potentiate anterior hip instability. Magnetic resonance imaging (MR-arthrography) should follow a dedicated protocol for the examination of the hip, including radial image acquisition or reconstruction and intra-articular application of contrast [27] to examine for intra-articular structures and pathology of both labrum and articular cartilage. Other causes for similar symptoms such as avascular necrosis, trochanteric bursitis or gluteal pathology can be differentiated. Additional measurements include labral size [13, 28] and iliocapsularis volume [29]. In these patients, we also advocate non-traction MR arthrography to examine for a accumulation of gadolinium known as a ‘crescent sign’ which is a subtle sign of instability on the axial view [30].

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF THESE MEASUREMENTS?

On plain films those measurements that are direct signs of instability are femoral head migration with an increase of the distance from the ilioischial line, a break in Shenton’s line and recentering of the femoral head on the AP view with hips in abduction and the FEAR index. On MR-arthrography the presence of Gadolinium in the postero-inferior joint space indicates migration of the femoral head and thus instability. The AI, NSA, AT, high iliocapsularis volume and increased labral volume may be present but are not predictive of instability [30] (Table 1).

WHAT ARE THE TREATMENT OPTIONS?

Treatment depends on the stability of the hip. The treatment alternatives for the painful borderline dysplastic hip include non-operative treatment, surgical treatment to address intra-articular impingement (FAI surgery by either hip arthroscopy or surgical hip dislocation) and surgical treatment to address instability (reorientation osteotomy with PAO and/or femoral osteotomy) (see Fig. 2). Non-operative management includes patient education, activity modification, simple analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and intra-articular injections [35]. Targeted physiotherapy can improve muscular conditioning, pain and proprioceptive control. The surgical treatment options for the borderline dysplastic hip which comprise arthroscopy and/or osteotomy will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

WHAT ARE THE RESULTS OF HIP ARTHROSCOPY IN THIS GROUP OF PATIENTS?

With the recent evolution in hip arthroscopy many surgeons are using this to address borderline dysplastic hips, not least because of perceived higher risks and longer post-operative recovery associated with alternative techniques such as periacetabular osteotomy. Hip arthroscopy in borderline dysplastic hips permits the surgeon to address intra-articular pathology such as a labral tear or femoral cam deformity [3, 12, 36]. If PAO is being considered to address the inadequate bony stability then arthroscopy may give the surgeon valuable insights not only into the intra-articular status of the hip but also how the patient is likely to fare with a much larger subsequent operation [37]. However, there is little published literature on hip arthroscopy in borderline dysplastic hips and what there is limited by short-term follow-up.

In the systematic review by Jo et al., 13 studies looking at arthroscopy in dysplastic hips were identified [10]. The studies were heterogeneous and all studies were case series. Only six studies reported on subjective and/or objective outcomes. The surgical indications for arthroscopy were ambiguous and patients had received variable non-operative management a priori. Furthermore the precise definition of borderline hip dysplasia varied and only two studies used the definition of Byrd and Jones [36]. Three studies reported on hip arthroscopy as an adjuvant tool and three as a stand-alone treatment. Labral tears had an overall prevalence of 77.3% and these were mostly located in the anterior or anterosuperior portion of the acetabular rim. Acetabular chondral lesions were more common than femoral lesions (59–75.2% versus 11–32%) and located adjacent to that of the labral pathology.

There were only two studies that examined the outcomes of arthroscopy in borderline hip dysplastic cases (LCEA 20–25°) of which only one described patient reported outcome measures. The latter, a prospective clinical case series by Byrd and Jones [36], had 66% of hips (32 hips) with borderline dysplasia. The mean modified Harris Hip score improved from 50 (poor) to 77 (fair) following arthroscopy. The authors concluded that the treatment response is likely a function of addressing the intra-articular pathology rather than the radiographic evidence of dysplasia.

WHAT ARE THE DANGERS WITH DOING HIP ARTHROSCOPY IN BORDERLINE DYSPLASTIC HIPS?

Arthroscopic labral resection and removal of lateral acetabular rim in borderline hip dysplasia can lead to fulminant joint instability [38]. Even if the labrum is repaired it is imperative to preserve the iliofemoral ligament and other static stabilizers of the hip to prevent the irreversible consequences or rendering the hip unstable [39–41]. There is no conclusive literature to support capsular repair in these cases but this seems a safe and sensible practice [42]. Capsular reduction techniques to improve stability have been described in borderline dysplastic hips [12]. If the hip is sufficiently unstable pre-operatively then addressing the intra-articular pathology alone by hip arthroscopy will be insufficient and the patient will require a PAO [43, 44]. One has to bear in mind that stability of the hip first line depends on the osseous geometry. In subtle instability (borderline dysplasia) stability may be secured by secondary soft tissue structures. Once these fail due to micro- or macrotrauma the hip becomes unstable. Restoring soft tissue stability may improve hip stability for a short period of time only, but it is likely that the soft tissues wear out again. Therefore the underlying osseous pathology has to be addressed first to achieve good long-term results.

A recent report showed an inferior hip specific functional outcome of PAO after failed hip arthroscopy in hip dysplasia [6]. Hip arthroscopy alone in this group of patients should be therefore approached with caution. However, it may have a role in those patients who are either unsuitable for PAO either because their hips are unfavourable (i.e. have a normal AI and normal femoral anteversion) or because their advanced age (i.e. >40 years).

WHAT ARE THE RESULTS OF REORIENTING PERIACETABULAR OSTEOTOMY IN THIS GROUP OF PATIENTS?

Acetabular reorientation via the periacetabular osteotomy has become the most common treatment for acetabular dysplasia with good outcomes reported at over 20 years postoperatively. Traditionally intra-articular pathology was addressed at the time of PAO by performing an anterior arthrotomy. However with the development of minimally invasive techniques for PAO this is no longer necessarily the case. Less invasive PAO techniques have decreased the time to postoperative recovery [45].

A recent study showed modifiable factors such as higher physical activity and higher BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 lead to a decreased age of presentation for PAO [46]. Furthermore patients also presented earlier for PAO with worse degrees of dysplasia: the LCEA was independently predictive of age at surgery, i.e. patients with a lower LCEA tended to require PAO surgery at an earlier age. However, there was no difference in outcomes following PAO between mild and moderate dysplasia. In this study mild dysplasia was classified as 15–25° which encompasses our definition of borderline hip dysplasia. A recent multicenter prospective cohort study that examined patient-reported outcome measures of PAO showed that, although overall results were good, improvements in borderline hip dysplastics and males were less than in those patients who had more severe dysplasia [47]. The authors discussed this with the danger of a small correction that may lead to overcorrection and iatrogenic FAI, increased femoral antetorsion and soft tissue laxity.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In borderline hips the crucial step is to define stability. Regarding the stability of the hip there are only two conditions: The hip is either stable or unstable. There is nothing in between. If this concept is accepted, the treatment gets comparably simple. Instability may be combined with other pathologies like FAI or overload/overuse and cartilage disease which need concomitant treatment. If the hip is unstable, acetabular reorientation is necessary. Addressing only worn out secondary stabilizers does not solve the underlying biomechanic problem and at best will yield satisfactory short term results. In stable hips, open or arthroscopic joint preserving surgery may be performed. However, we have to keep in mind that each degree decrease of the LCE angle below 28° is associated with a 13% increase of osteoarthrosis [20]. Therefore, if in doubt, in order to maximize the chance of good long-term results, we would advocate for an acetabular reorientation operation.

It is important to identify the areas where we lack knowledge in order to guide further research. Longer-term follow-up studies comparing acetabular reorientation and hip arthroscopy in these patients, ideally in which all imaging parameters and Beighton scores are recorded would be performed. In addition patient-reported outcome measures and time to recovery and resumption of activities including sport should be attained.

文献出处:Michael C Wyatt, Martin Beck. The management of the painful borderline dysplastic hip. Review J Hip Preserv Surg. 2018 Apr 5;5(2):105-112. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hny012.

本文是陶可版权所有,未经授权请勿转载。本文仅供健康科普使用,不能做为诊断、治疗的依据,请谨慎参阅

评论